The first abused glamour. The second abused money. The third abused power. They became a triune of impunity, but they thrived in the tribunal of a vain and idolatrous generation.

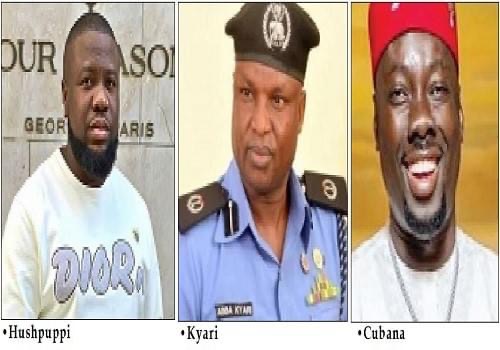

The stories of Hushpuppi, Obi Cubana and Abba Kyari only show how they make a mockery of money and hard work in this country. They were the odds and ends of the Nigerian contemporary culture, the alliance of decay. Ironically, they are not on the fringe of society. The likes of them have become the mainstream. Those who pissed on the river’s edge have polluted the whole body of water. The fishes now bob as lifeless creatures on the ebullient streams.

When they began, they etched their tales as epic. They now ebb as anti-climax. They were models of class. Now they seem like yokels. Instagram sizzled with their faces and poses and quotes. Now they are footnotes and distorted memories. Everyone wanted them who robed them as winners. Now some worshippers are wincing in existential doubt. They were online idols. A million eyes bowed, clicks were rites, shares evangelised, likes were the amens and envy were the iniquities.

The first was Hushpuppi. His narrative for this essayist was his subversion of the work ethic. Ramon Abbas emerged from the dark but all over him was a cloud of confetti. They called him Gucci Master, a toast of the internet. The young followed him, cursed and envied him. Few asked how he became so rich that he draped himself in the high-octane waves of brands: Gucci, Fendi, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Jimmy Choo, et al.

This is the sort of brand most people save for years to purchase. Even at that, they get one item and savour it, be it a bag, a pair of shoes or even a shirt. I recall in Paris years ago, I saw a Chinese lady who planted herself outside the window of a Louis Vuitton store long after it had closed for the day. She was ogling an item. The lust flamed through her soul. She was like an engrossed somebody spying her beloved. Obviously, she could not afford it at that time. She was probably saving, and hoped she would be ready in time before the item evaporated from the rack. Our man Ramon hauls them home like a trawler of fish.

But the paradox is that Hushpuppi thought he was working hard. Indeed he was. A Bloomberg report showed the mockery of industry that attends his work. It was often a triumph of intelligence monitoring, internet acumen, psychological scheming, data processing, mastery of timing, a finger on the pulse of the market. It is a genius at work. He understands the geography of money movement in the work, the policies of banks, the politics of each country, the soft underbelly of the financial world. He knows when to pause, when to parry, when to decoy, when to strike. Like a marksman, he marshals all these into a flawless shot at a deal. When he sunbaths beside his pool, he is celebrating his diligence. It is the sincerity of a conman.

That is why people like him have distorted the work ethic. He was a conman who was different from the pen thief in the ministries. Those only need to sign and doctor figures. For Ramon Abbas, it took racking of the brain.

So, they see themselves as the real thing. But they are parodies of work. It is wealth without industry, profit from the devil’s plate. It is like George Orwell’s short story titled A Hanging, in which all the executioners employ the normal language of a workaday labourer, like a farmer or fisherman, when they execute a fellow man. Men like Hushpuppi would quote Christ when he said “a labourer is worthy of his hire.” But even in that Bible passage, he warned against greed, and forbade his disciples to go from house to house. Hushpuppi travelled from brand to brand, from Gucci house to Chanel shine. He lived not for the brand but for his brand. He conjured Hushpuppi and its glam for instagram. Instagram was his arena, his stage. How many times did he wear them? Where did he go? He had no mainstream skill. No one invited him to a conference, or to give a speech, to a black-tie event. His office was languor, not glamour; in the bedroom where he could hide only in underwear and mint millions of dollars.

For Obi Cubana, this essayist is not interested in how he made his money, but how he spent it. Especially when his mother passed, in a town known as Oba, which in some places means king. He played obscene royal for his mother. The comedian Elder GCFR warned all those females trooping to the Oba of Benin’s palace to not confuse the Oba of Obi Cubana with the grand abode of their monarch. The laugh merchant was referring to females at the party, where money was turned into a gutter. Those who make money through sweat, who belabour bone and blood, should think twice about the display of squander. Those who have many times more money are not seen in other climes to descend to such vanities. It was in a village, I learned, where many would want to send their kids to good schools, where many may not have the square meals they desire, where schools and hospitals could have been memorialised in his mother’s name. Now the memory for the poor woman is money baked in dust and slime, much of it unspendable. No legal tender for mama. Rather than being a burial of remembrance, it was a memorial of superfluity.

Wealth comes with responsibility. No one makes money out of a vacuum. The society demands, at least, a dignity of success. What happened at Oba was a subversion of merit. In Warri, in my young days, we called it money miss road. His is the sort of reckless splurging that Scott F. Fitzgerald documented in Jay Gatsby, the main character of his novel The Great Gatsby, who threw parties of extravagance and everyone, most of whom he did not know, attended. He never connected with his guests. The person across the street he wanted to connect with and impress never came to the party. It is the futility of such self-indulgence, making money the be-all and end-all of society, just like the old Dickensian woman in the novel, The Bleak House, who thought whenever a person mentioned a figure it must refer to money.

Abba Kyari was the supercop who has been associated with both men. A supercop who gyrated at parties, who glorified stunts, who witnessed Obi Cubana’s vanities even as he broke the law by “spraying” money, and did nothing. It is he who now has to explain why he had a team that emboldened a crime with a crime. Now the fault lines of his character are in the open. In the FBI report, Hushpuppi expresses himself in a righteous tone, and the supercop obliged.

The story of the three is the story of how tribe matters little when money is involved. No one thinks Yoruba, Igbo or Fulani in the three. Money has no tribal fealty. It does not speak a language in the market. The story also tells Nigeria’s materialistic turn. Hushpuppi represents making money no matter how. Obi Cubana wasted it no matter how much. And Abba Kyari endorsed them from the high quarters of the law for whatever they were worth.