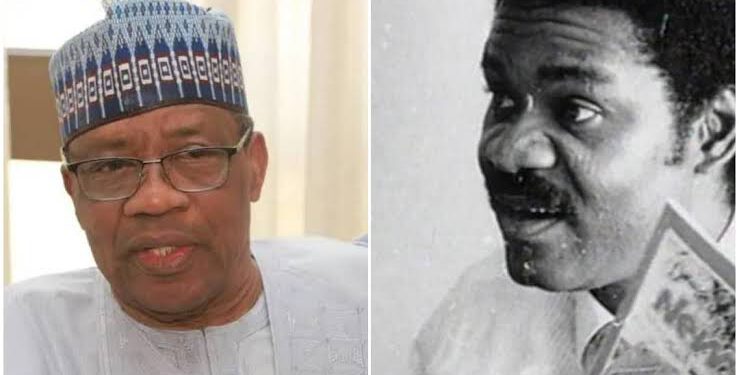

𝐵𝑦 𝐺𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝐼𝑏𝑟𝑎ℎ𝑖𝑚 𝐵𝑎𝑏𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑖𝑑𝑎

“On October 19, 1986, the charismatic and famous journalist Dele Giwa was killed by a parcel bomb that was delivered to his Ikeja home by yet unidentified couriers.

Reports from initial eyewitnesses, the police and preliminary intelligence analyses on what happened were shocking and confusing.

His security guards handed the parcel to Mr Giwa’s son for onward transmission to his father. Dele Giwa was at his breakfast table with Mr Kayode Soyinka, the London Bureau Chief of Newswatchmagazine. The parcel reportedly exploded on being opened and blew the lower torso of Mr Giwa to pieces. Dele would later die from his wounds in a hospital.

The novelty and tragic impact of the incident badly shook the nation. I was equally shocked by it all. On a personal level, I had just lost a friend. Mr Giwa was a good friend, like a few other senior journalists in the country. We spoke often on the phone and met a few times. I valued his deep insight on national issues and respected his views and reach as a media leader. My sense of loss was, however, overwhelmed by the public outcry and the feeling of tragedy in the introduction of an entirely novel mode of killing in our country.

Coming a few weeks after the OIC crisis, which led to the retirement of my number two, Commodore Ebitu Ukiwe, I saw Giwa’s wicked and cruel murder as part of a series of booby traps and acts of destabilisation being hatched against the administration.

Undoubtedly, our choice of the path of rigorous reform had earned us unintended adversaries. I tried to understand the implications of what had just happened by making sense of it. I analysed and tried to interpret the incident first at a personal level. Whoever was the mastermind knew my relationship with Giwa and a few senior journalists. Hitting at Giwa would get to me emotionally.

Secondly, Giwa was a very popular and colourful journalist, a person of great public interest for anyone wanting to inflict a mischievous political blow on the young military administration.

Giwa was loved by his audience and the rest of the public. Targeting him would shock the public and paint the administration in a feeble light. The insinuation that the parcel may have come from the headquarters of the administration was cheap and foolish. Why would an officially planned high-level assassination carry an apparent forwarding address of the killer? Why would a government-planned and executed crime point directly at the suspect? All this did not make sense to me.

Much as this incident rattled me, I also accepted and understood it to be part of the challenges of the task I had taken on. I was responsible for acting in the public interest, but only in the context of the institutions and mechanisms of government. I had no alternative but to resort to the state’s investigative apparatus. The police and the intelligence services were all I had to rely on.

I promptly ordered the Inspector General of Police to assign the best possible investigative team to the case and report to me daily. I also instructed the State Security Service and Military Intelligence to recall all recent encounters with Mr Giwa and other senior journalists and submit a detailed report to me promptly.

The Newswatch management took recourse in the law by taking the murder case to court through their lawyer, Chief Gani Fawehinmi.

However, the Newswatch team’s recourse to play to the gallery of public sentiment did not help the case. Directing public focus to only one suspect, namely the administration, may have hurt the path of a fruitful investigation. In any credible crime investigation, you limit the chances of success by limiting the circle of suspicion to only one direction. Worse still, when a crime is committed, to ascribe an exclusive political motive to what should first be a criminal act never helps. It helps the real criminals escape the political smoke and cloud.

The involvement of high-profile lawyer Gani Fawehinmi and the populist slant given to the case by the media poisoned the investigation with political overtones. The investigation into the Giwa murder became part of the tools in the armour of a growing political opposition targeted at discrediting the military over the planned political transition programme and human rights issues.

The legal drama and political grandstanding combined to muddle the work of the police and intelligence investigators towards getting a factual report on this cruel and criminal act. What the campaigners failed to realise was that even under a military regime, crimes will be committed by persons and agencies that may not be directly related to either the military establishment or the government. The best way to cover up for heinous crimes would be to craft them in a manner that includes the government among the suspects so that what should ordinarily be a criminal investigation is drowned by political actions and populist sentiments.

Despite this initial unfortunate distraction, I chose to keep an open mind and encourage the police and other investigative agencies to do their best to unravel the murder, given the enormity of the public interest in the matter. While the accused military officers resorted to legal action to protect themselves and their careers, the police team went ahead with its investigations; the Supreme Court’s suggestion that the Newswatch lawyer, Chief Gani Fawehinmi, could take on the case as a private prosecutor did not receive a positive response.

The hysteria of the media did not help the investigation of the Giwa murder. As is typical of the Nigerian media, the direction was marked by an adversarial attitude towards government, which has remained the hallmark of the Nigerian media from its colonial heydays. It was an attitude of ‘we versus the government’ that has remained today. It is a situation in which the government is adjudged guilty even before the evidence in a case is adduced.

When the Obasanjo civilian administration reopened the Giwa case at the Oputa Panel on Human and Civil Rights, I expected that the police and lawyers would come forward with new evidence as to their findings on the Giwa murder over the years. Nothing of such happened. The Giwa, like all mysterious murders, has remained unsolved after so many years. I keep hoping the truth will be uncovered in our lifetime or after us. More often than not, mysterious crimes are solved long after their commission.”

𝐶𝑢𝑙𝑙𝑒𝑑 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐵𝑜𝑜𝑘: “𝗔 𝗝𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗻𝗲𝘆 𝗶𝗻 𝗦𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗶𝗰𝗲 – 𝐀𝐧 𝐀𝐮𝐭𝐨𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐩𝐡𝐲” 𝑩𝒚 𝑰𝒃𝒓𝒂𝒉𝒊𝒎 𝑩𝒂𝒃𝒂𝒏𝒈𝒊𝒅𝒂